The Library Is Dead. Long Live the Library!

When it comes to discussing the future of libraries, words get in the way. More accurately, books full of words (and rooms full of books) get in the way.

The evolution of libraries and books share a common, intertwined history. But it’s this association with books as the raison d’etre of the library that feeds the illusion of the library’s pending doom. Technology is ever introducing more convenient, instant, affordable, precisely calibrated paths to retrieving the written word. In the face of this, the 560-year-old “technology” of the printing press is a necessary but no longer a sufficient foundation on which to design an enduring institution.

On this, the public library’s champions throughout history would agree. They consistently emphasized the library as a force for progress. A prerequisite for effective democracy was an informed citizenry with a thirst for knowledge, and a forum to share ideas. They also recognized it as a democratizing force in a different sense – an instrument to promote social and cultural (as well as functional) literacy where, in the words of the Andrew Carnegie whose philanthropy built 2,500 libraries, “neither rank, office, nor wealth receives the slightest consideration.”

Now that is a concept as radical today as it was a century ago.

RE-INVENTING THE LIBRARY

Let’s define a vision for our library-of-the-future that embraces this broader mission, and leaves the word “book” out of it: The future library is a forum for knowledge and ideas that promotes community, democracy and equal access. It is an ever-adapting instrument to promote cultural, social, and technological literacy going forward, while serving as a time capsule allowing us deep insight into the past.

To accommodate this vision, our library needs the agility to adapt, and entice you and your descendents to return time and again. And what lucky citizens you will all be! Like never before, massive information availability will be a given in an age when the contents of a million books can fit on a device you carry in your pocket.

So perhaps it is the curating of this information landslide, plus sophisticated search-and-find tools, and public availability of subscription-based knowledge hordes that will be the baseline of even the smallest library. Meanwhile regional and international connections – especially those that engage in multi-cultural, multi-media and multi-dimensional ways – will be the minimum requirements on your path to enlightened citizenship.

Counterbalancing this dizzying array of resources, your future library must also nourish knowledge at the most local levels. Futurist Thomas Frey imagines libraries serving as vital “time capsules”, the sole remaining repository of long-shuttered local newspapers, film-based photography, and local broadcasts. But how these stories are conveyed would be more akin to today’s most interactive museum exhibits, allowing tomorrow’s youth to experience the flavor, rituals, sounds and formative cultural moments of past eras in each town.

DESIGNING THE LIBRARY

But how do we design an edifice that accommodates an ever-shifting mandate? For starters, we should not be defining our library so much by what it houses, and more by how it houses.

That is the adjective-filled language of architecture.

It might mean a mix of spaces: one playful, another inspiring; one studious, another conspiratorial; a serene, meditative room, and a stimulating, sensory-rich, invigorating one; an airy and sociable space; a cozy, intimate nook.

Gardens, courtyards, or amphitheaters might create more flexible “rooms” that provide untethered learning opportunities in an outdoor forum.

This architectural agility is perhaps most indispensable in the smallest communities. An example is in the works in the Finger Lakes town of Lodi, population 1,500. The community has been working for two years with architects to envision a new library that meets these challenges. Conceptual renderings on the library’s website reveal a building in which a series of rooms cascades irregularly down the sloped site. They are connected by ramps that encourage full exploration of resources, and link spaces of varied character whose functions might change over time.

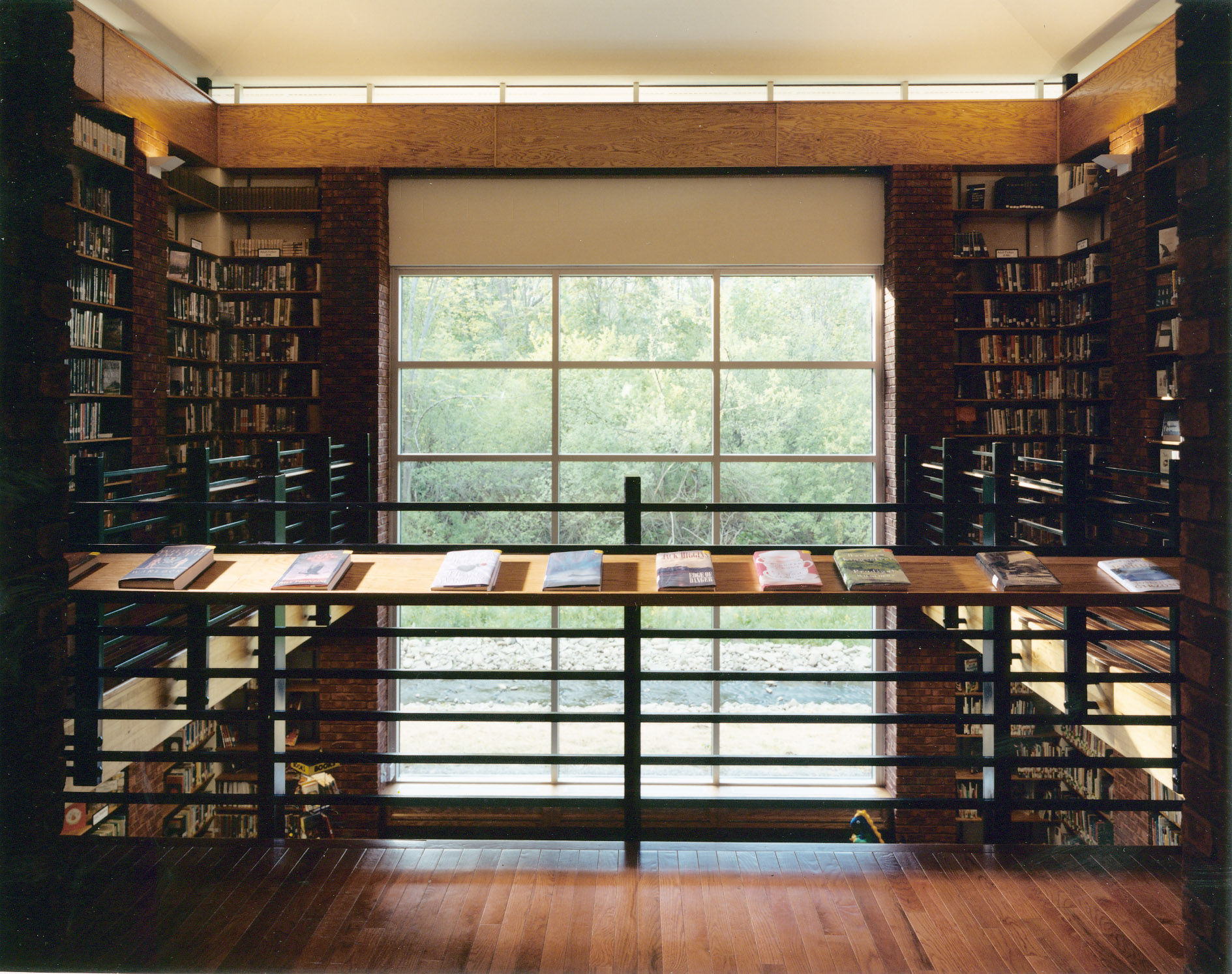

For me, a starting point can be found in one of my first completed projects for a library in Castile, a town of 2800. Its naturally-lit, balcony-wrapped children’s room was conceived as “a pavilion-in-the-woods” with a generous window to the forest. Envisioned as a place for storytime and imagination, its walls of books define – rather than fill – what is essentially a flexibly designed space. In my visits over the past ten years, I have witnessed that space adapt for town hall meetings, quilt exhibits, films, lectures, chocolate tastings, auctions, fundraisers and American Doll tea parties to name a few. Might it be a venue for a holographic re-enactment of the Gettysburg address on its 200th anniversary in 2063? It could.

If these examples indicate anything, it is that the future library must not simply address the changes technology has wrought on how we consume information. It must transcend them.